On September 12, IMAX Melbourne made its debut screening of an Indonesian film, to the excitement of many, as the honor went to a highly anticipated horror movie.

The theatre, the largest IMAX in the southern hemisphere, screened Badarawuhi di Desa Penari, the long-awaited prequel to Indonesia’s highest-grossing film KKN di Desa Penari, fueled by the enduring popularity of the horror genre among Indonesians, both at home and abroad.

“As the first Indonesian movie Filmed for IMAX, … [it] offers a fresh twist on the horror genre that we think our audience will really enjoy,” a spokesperson said, quoted by the ABC.

“We’re hopeful that the distinctive storytelling of Indonesian horror will similarly find a mainstream audience [in Melbourne].”

Indonesian horror stories, rooted in local myths and folklore, persist because of their deep familiarity.

Experts say belief in the ethereal is ingrained in the Indonesian psyche, passed down through generations in a tradition of oral storytelling.

For Arini Suryokusumo, a Sydney-based Indonesian horror story writer, it has become a way for Indonesians abroad to share their identity in a way others may understand.

“We’re sharing our culture with the world through new lenses, showing how our storytelling has developed while still holding onto what makes it unique – supernatural power,” she told The Perantau.

To her, the horror aspect has faded away over time. Rather, she reads and retells Indonesian horror folklore for the memories it invokes.

“I grew up listening to these stories,” she said.

“They connected me with my family, especially my grandmother. She used to tell me these stories before bedtime.”

Arini’s childhood memories of bedtime stories mirror the experiences of many Indonesians abroad.

These tales are not only personal recollections but also resonate with a collective cultural memory that unites the diaspora, linking them to shared experiences of growing up in an environment steeped in the supernatural.

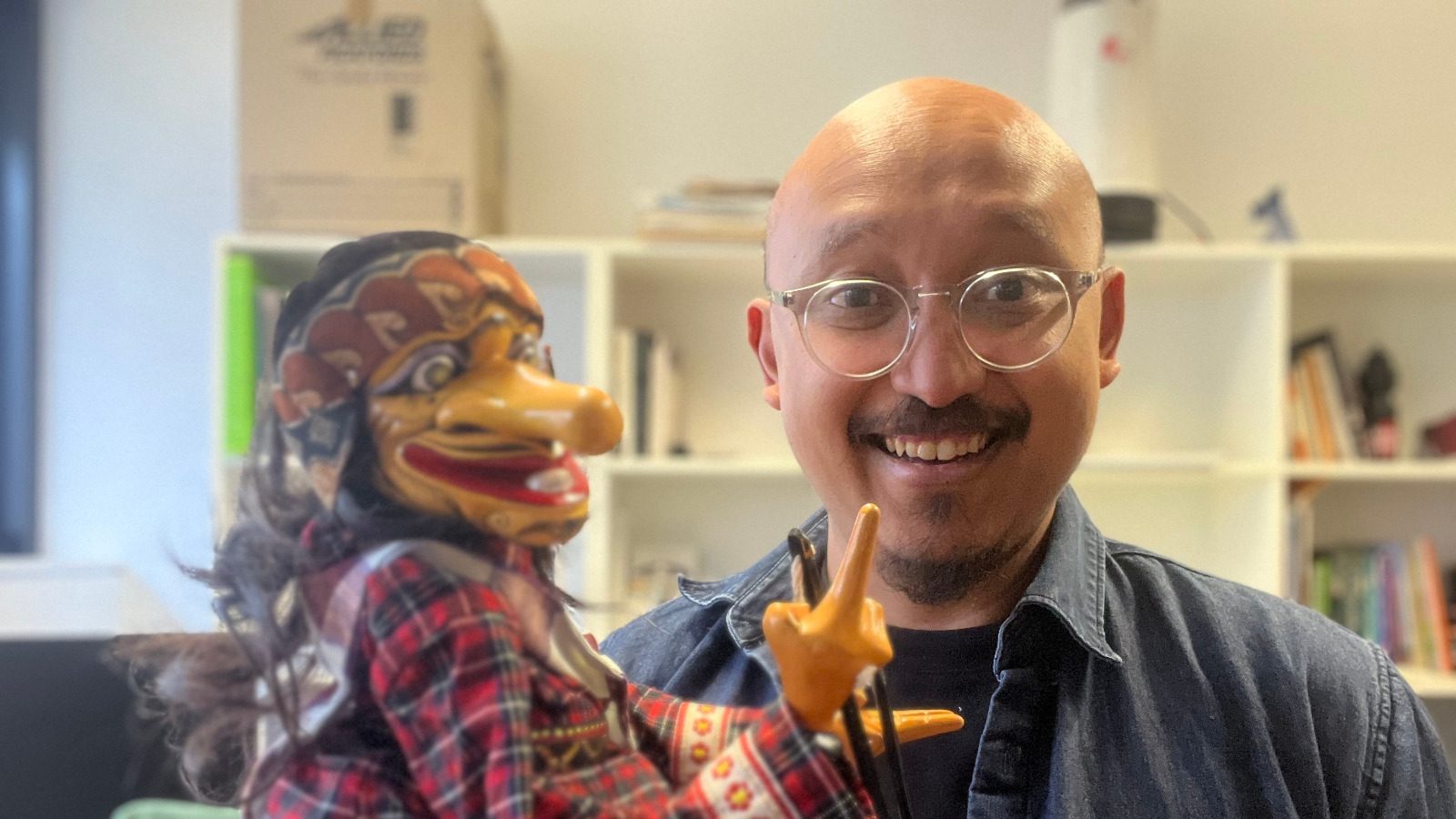

This nostalgia is especially potent for those abroad and exposed to a mix of cultures, said Tito Ambyo, an RMIT lecturer researching Indonesian digital horror and folk stories.

“A lot of these things really shape the way we think about the world, and they shape the way we think about the world in quite deep ways as well,” he explained.

They serve as a bridge to cultural traditions and values that might otherwise fade with time.

By engaging with these stories, younger generations of the diaspora can understand their cultural background, while older generations find a comforting continuity with their past.

They engage with a cultural narrative that helps preserve a sense of identity, even as they live far from home.

Uniquely Indonesian

Research from The Australian National University found that despite the growing global exchange of culture and media, Indonesian horror remains uniquely tied to local contexts.

It plays a distinct role in reflecting societal values and norms, often sparking debates around morality and taste.

The genre, although frequently criticised at home, serves as a platform for reigniting cultural stereotypes and highlighting social divisions within Indonesia itself.

The guise of fear and tension in horror storytelling offers a broader reflection of Indonesian society, serving as a powerful medium for diaspora to confront historical trauma and cultural memory.

“If you look at many folk stories around the world, including Indonesia, many of them come from real problems that people are facing,” Ambyo said.

“Like the riots in 1998, and 1965-66, we have all this stuff that happened in our history, and we’re kind of unsure how to talk about it.”

“Using ghosts and horror, we can discuss these issues without directly referencing the violence itself.”

Just as horror allows the diaspora to indirectly engage with historical events like the 1998 riots and the 1965-66 purges, the tales of kuntilanak and sundel bolong reflect deeper anxieties about gender inequality and violence against women, for example.

Indonesian horror traditionally often portrayed women as either helpless victims or evil beings.

Female protagonists often died after suffering abuse, with life after death enabling their return as vengeful spirits seeking supernatural justice against their tormentors.

Figures like kuntilanak and sundel bolong, for example, were canonised as women who died at childbirth.

These women “were victims of gender inequality”, “sexual violence” with “poor access to healthcare”, explained Gita Putri Damayana from the Indonesian Center for Law and Policy Studies (PSHK).

“The popular ghosts’ stories reveal the close connections between violence against women and access to healthcare for women in the distant past,” she wrote in The Conversation.

“The plights of these women ghosts, as told by the older generations, serve as a warning about the state of Indonesian women today.”

Arini says that while these stories may be outdated in their portrayal of gender roles, they are also a reminder of our past and a tether to our identities.

The gradual evolution of horror stories and its representation in Indonesian pop culture is something that she takes pride in as it blends “contemporary culture with traditional supernatural beliefs.”

“We need to embrace it, that was the way used to tell our stories,” she said.